Connecticut Children’s Ambulatory Surgery Center in Farmington provides a range of benefits for families in Connecticut. The surgeries are all outpatient and tend to be relatively common procedures. Being in Farmington, it’s closer for families in the southern and western parts of the state, it offers easy access and parking, and provides top-flight surgeons, nurses and clinical staff performing a broad array of surgical specialties. That diversity was on display on the day in August that we visited the center, when 23 children were scheduled for operations ranging from repairing crossed eyes to rebuilding a torn ligament. The first families arrived around 6:00 a.m., the first procedures started at 7:00, and all three operating rooms were constantly in use well into the afternoon. Here, we present some glimpses of that busy day and the children who were healed.

7:00 a.m.

The light-filled waiting room is pretty full, with children of various ages and their parents. Neither the kids nor the parents seem particularly anxious, despite the fact they are all facing surgery. Two of the young girls have arrived in full princess regalia, including crowns, adding to the sense that these procedures are no big deal. And, of course, there are a fair number of large stuffed animals along for the ride. It speaks well of the quality of care here that two of the other patients scheduled for surgery today are children of Connecticut Children’s team members.

Abigail is a 17-year-old who loves sports. She plays soccer and volleyball, and last year, she started playing basketball. After a fall, she felt her left elbow wasn’t working correctly, interfering with her game, despite trying splinting and therapy. She’s here today to have corrective surgery for that elbow. In the pre-op area, nurses work with her and her family to prepare them for the surgery, physically and mentally. Here in the center, nurses are even more essential than they are in most facilities. They care for the kids in pre-op and post-op, manage the parents’ concerns and, basically serve as nurse, child life specialist, and social worker all wrapped into one.

Once the preparation is complete, Abigail is wheeled into operating room two, and the surgical team goes to work. The problem Abigail was having involved her ulnar nerve, which travels from the neck down through the arm to the hand. Where the nerve passes the elbow joint, it can sometimes become constricted and unstable, which causes pain and numbness. The solution to this problem is to release and move the nerve to a different location where it will not be stretched.

Abigail is anesthetized and her left arm is prepared. Division of Orthopaedics surgeon Sonia Chaudhry, MD, made an incision and exposed the nerve, protecting all its small branches. Then, she very carefully moved the nerve to the top side of the joint, where it could function unencumbered, and secured it there. The whole procedure took about an hour and forty minutes to complete—one of the longer operations at the center.

9:30 a.m.

In operating room one, 17-year-old Layla is having a torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) addressed, a procedure performed regularly at the center. She arrived on crutches and in a leg brace, and rather than being anxious about surgery, she was eager to have it done so she could regain her former mobility. The ACL holds the bones of the knee together, and while the surgery is commonly performed, it is not simple. The ACL usually cannot be repaired, so it must be replaced. The standard approach is to harvest a piece of a tendon elsewhere in the body (the quadricep tendon is the one used most of the time at the center) and replace the broken ligament with the new tendon. This morning, the surgery is being performed by Allison Crepeau, MD, from the Sports Medicine division.

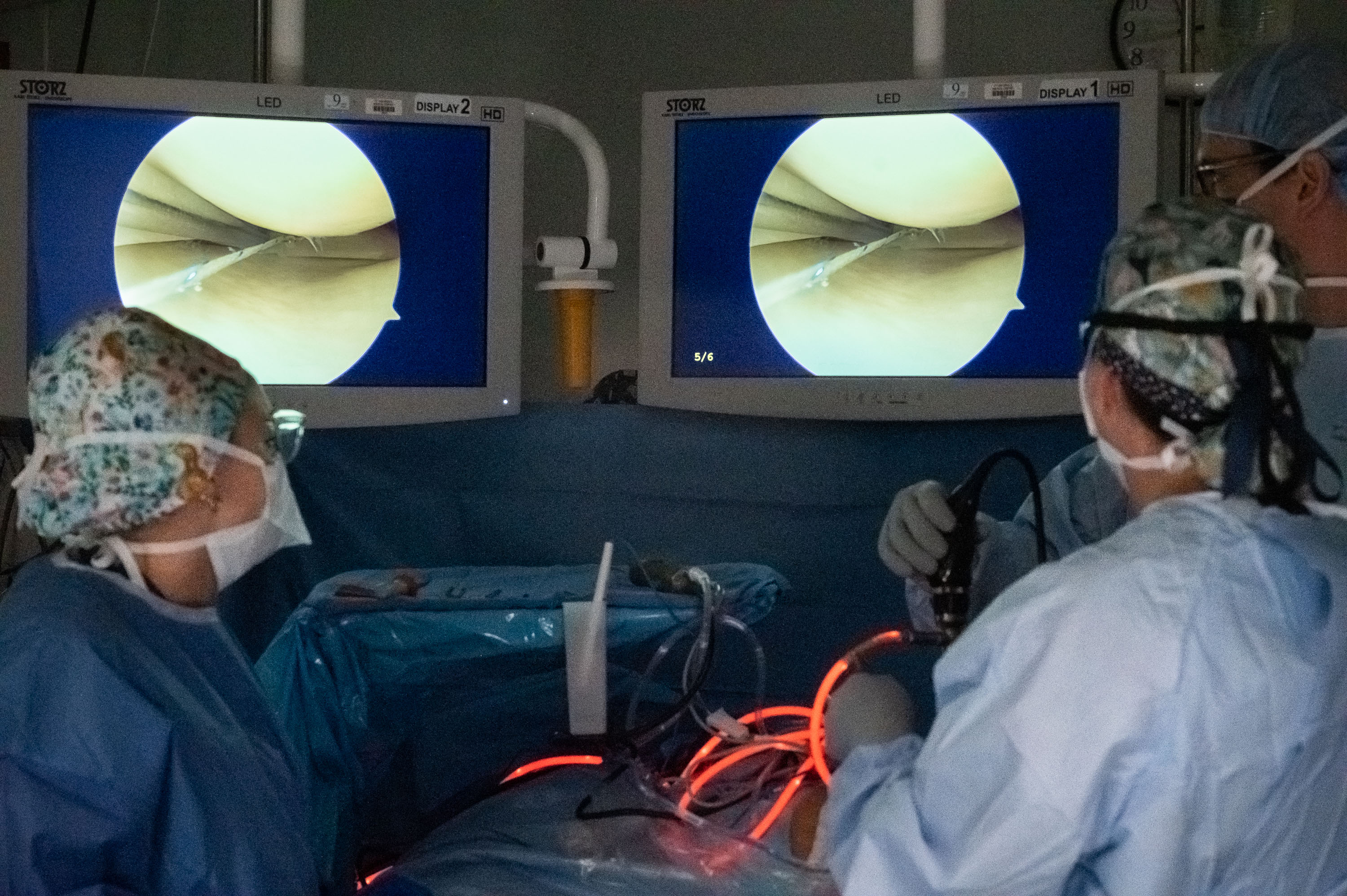

Once Layla is anesthetized, Dr. Crepeau cuts out the piece of tendon they will be using and then bends her leg so the knee is upright and forward. Then, after marking the site for the incision, she cuts two small holes in the skin and inserts two tools. One is a camera and light, so she can see what she’s doing with the other tool, which looks a little like a Black and Decker hand drill. And in fact, Dr. Crepeau uses that tool to drill holes in the bones so the new tendon can be attached. The camera is attached to two computer monitors above the operating table, and Dr. Crepeau watches those monitors to see what she’s doing. While she’s doing that, Katelyn Colosi, PA, is preparing the tendon on a nearby table. It’s stretched tight on a rack, and the clinician uses tough thread to bind it and wrap it, to give it maximum strength. Those threads extend out from the ends of the tendon and allow the graft to be fixed in place and tightened to the correct tension.

Once the holes are drilled and the tendon is prepared, Dr. Crepeau feeds the ends of the threads through the holes in the bones, securing them with screws. Then she x-rays the knee to be sure everything is in place as it should be. Finally, she sews up the small incisions and prepares for the next case. This sort of ACL repair is major surgery, and rehab will last for most of a year, but then Layla should be up and running, as good as new.

11:30 a.m.

Next we encounter a quiet six-year-old girl with haunting dark eyes. Her father is stoic, and the child herself is not given to chatting. She’s here because she needs some reconstructive surgery done on her teeth. She is in operating room two, where Ammar Idlibi, DMD, a pediatric dentist, will do the surgical work. He bends very close over her open mouth, working with intense concentration and a variety of tools. Because he’s working on her mouth, she cannot have a breathing tube down her throat, as most other patients do. Instead, the team has set up a tube that runs to her nose. Her surgery takes a little more than an hour and a half to perform and is entirely successful.

1:30 p.m.

Twelve-year-old Zak is a bright, outgoing boy with a lot to say. And that’s just as well, because the surgery he’s getting in operating room two requires him to be awake during the procedure and conversing with the surgeon. Dr. Chaudhry will be performing a WALANT surgery—the acronym stands for wide awake, local anesthesia, no tourniquet. There are several benefits to this technique, but the biggest one is because the patient is awake, he or she can respond to the surgeon’s questions. That, in turn, means the surgeon can get instant feedback about how a given procedure is working.

In Zak’s case, he has a ganglion cyst in his right wrist, and when Dr. Chaudhry removes that cyst and takes steps to prevent future recurrences, she needs to know whether or not the change is working. That means he needs to be awake to respond to her. Zak is lying on his back on the operating table, and his left arm is extended onto a shelf where Dr. Chaudhry can easy work on it. The team has hung a sterile sheet vertically by his left side so he can’t see Dr. Chaudhry or what she’s doing to his wrist. As she works, Dr. Chaudhry is having an ongoing conversation with him, about everyday things, mostly. It’s a strange thing to watch her grab a tendon and pull it up out of his wrist to move it while he is chatting away oblivious on the other side of the sheet. Once she has things where she thinks they should be, she asks him to move his fingers and hand, to test it. And, happily, everything works beautifully. She sews up the incision, and Zak hops off the table and, after a brief stop in post-op, goes home.

By the end of the day, all of the princesses and other patients have had happy outcomes and gone home, helped and healed. And the staff prepares to do it all again tomorrow.

Invest in a Better Future

When you give to Connecticut Children’s, you make an investment in pediatric health and better futures for children. Healthier children grow into healthier communities. At Connecticut Children’s, no child is denied care based on a family’s ability to pay. We are here for anyone who needs us…maybe even you.

Latest Articles

How HuskyTHON Student Leaders Are Changing Lives

Matters of the Heart: Cardiac Telemetry Saves Kids’ Lives